Running into history

01 April 2008, 7am UTC

A pioneering project

On 19 March 1978 – it was Palm Sunday – an event staged in Atlanta dramatically heightened international awareness of women’s distance running and the desire among women runners for their own long-distance events to be included in the Olympic program.

It was the Avon International Women’s Marathon. Funded by the well-known manufacturer of health and beauty products, it was the first in a series of seven marathons held annually around the world that provided a global stage for women to demonstrate their talent at distance running.

In 1981 the International Olympic Committee announced that a women’s marathon would be part of the 1984 Los Angeles Games program, and there is little doubt that the first four Avon marathons provided particular impetus for this decision. Held in such diverse locations as Atlanta, Waldniel (GER), London, and Ottawa these races drew runners from as many as 27 countries on five continents.

Earlier in the 1970s Dr. Ernst van Aaken, a coach and physician who lost both legs in a running accident, had lobbied hard for a women’s 1500m event in the 1972 Munich Olympics. In the late 1970s he organized three international women’s marathon championships in his home town of Waldniel. The Avon Corporation, the world leader in cosmetics, fragrances, and fashion jewelry, was keen to promote fitness among women as an integral part of the notion that health and beauty go hand in hand. They decided to organize road races, at a variety of distances, in all the countries in which Avon did business. The winners of shorter distance races would be eligible for an expenses paid trip to the annual extravaganza event – the international marathon. Katherine Switzer, known as the female runner who was almost bounced out of the 1967 Boston marathon (before women were officially permitted to run in 1972) was hired to develop the concept and oversee the entire Avon running program.

Atlanta was selected as the first venue because Avon had a large headquarters there. It was logical for Waldniel to be the second venue in honor of Dr. van Aaken’s efforts. Every race was well attended, clearly demonstrating that women’s marathon running was worthy of Olympic status. This was understood by Olympic officials as well; it simply needed to be documented.

As local Long Distance Running Chairman for the USA’s Amateur Athletic Union, I served as a liaison between the national governing body and the race organizers. I wrote to Monique Berlioux, then Director of the IOC, asking her to attend the Atlanta race. “I am most sorry to miss this occasion which I am certain will prove very exciting and a positive boost to women athletes,” she wrote on 7 March 1978, “who – you will forgive me for adding – are as much, if not better, suited physiologically than men to long distance running, although to date races for women have tended to be fairly short.”

In the Atlanta race, little-known Martha Cooksey, 23, running her eighth marathon, came from behind in the later stages to defeat a field that had 17 of the world’s top 24 women marathoners. Runner-up was Hungary’s Sarolta Monspart, first European under three hours, and the first woman distance runner from the Eastern bloc of nations to compete in the West. Third place went to Germany’s Manuela Angenvoorth, who was one of Dr. van Aaken’s runners.

Unusually warm weather slowed finish times in the Waldniel race. Coach Bryan Smith brought two of his star pupils from the Barnet Ladies Athletic Club: his wife Joyce, aged 41 finished more than three minutes ahead of 24-year old American Kim Merritt and 35-year old Barnet teammate Carol Gould.

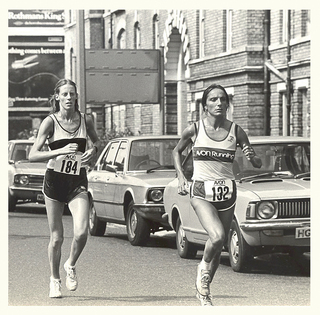

In 1980 the Avon race closed down central London streets – the first time this had ever been done for an athletic event. The race was on 3 August, just two days after the Moscow Olympic men’s marathon. That 27 countries sent athletes, spanning five continents, demonstrated the appropriateness of Olympic status. The event was televised worldwide by both the BBC and NBC. Despite another warm day, Lorraine Moller ran a personal best to win, as Nancy Conz (USA) was fast closing down on her.

The course in Ottawa, for the fourth edition of the series, started and finished near the downtown Parliament buildings. After crossing the Ottawa River into French-speaking Quebec, the route returned to Ottawa and went out-and-back alongside the 150-year old tree-lined Rideau Canal. Runners appreciated the shade but temperatures still reached 20C, with 80% humidity thwarting attempts at personal bests. Nancy Conz, a 24-year old running shoe sales clerk took the lead at 5km and won with 2:36:46. As she slowed towards the finish Joan Benoit came within half a minute of catching her. Third place went to an unknown 19-year old from Cincinnati, Julie Isphording, who later represented USA at the inaugural Olympic women’s marathon in Los Angeles which Benoit won. Every competitor had reason to celebrate as this was the first all-women’s marathon since the IOC voted (on 23 February 1981) to include a women’s marathon in the 1984 Los Angeles Olympics.

At the post-race party 80-year old Ruth Rothfarb of Miami Beach took to the dance floor with surprising energy after her 5:39:57 marathon debut. She became the oldest woman ever to have finished a marathon. An interesting outgrowth from this marathon was the onset of an extensive polemic in running magazines about age limits. Is a marathon too risky in terms of musculoskeletal injury for people as old as Rothfarb, or as young as 11-year old Jennifer Amyx, whose Ottawa race was her eleventh marathon (she finished 46th in 3:02:58)?

Both of these women entered races for fun, as a celebration of fitness rather than a competition against time, which may explain their lack of injuries. However, the potential problem of injury from repetitive impact stress to the growth plates of the lower limb bones among runners under 18 remained of concern. A paper by IMMDA (the medical affiliate of AIMS) in the fall of 2001 recommended that race directors prohibit runners under 18 from entering marathons.

After the Ottawa race, and the IOC announcement, other women’s-only championship-quality marathons started up, and increased the racing opportunities for both developing and experienced women marathoners. Three weeks after Ottawa came the first women’s-only European Marathon Cup competition in Agen, France (won by Zoya Ivanova in 2:38:58). The first Osaka International Ladies Marathon was staged in January 1982 and was won by Italy’s Margherita Marchisio in 2:32:55. This was the third major women’s-only race staged annually in Japan, after Nagoya and Tokyo.

The 5th Avon Women’s Marathon Championship in San Francisco featured the grandeur of crossing the Golden Gate Bridge but made the course too hilly to achieve fast times. Avon London winner Lorraine Moller won an exciting struggle over Ireland’s Carey May, a 22-years-old computer science major at Brigham Young University. Rules still did not permit direct prize money, but “developmental money” was available to be placed in a trust fund, and Moller earned $15,000 for her victory.

The 6th Avon International Marathon was greatly enhanced by incorporating the US open and masters championships for 1983 and acting as the US selection race for the first-ever IAAF World Athletics Championships in Helsinki. It was also a rehearsal over much of the Olympic Marathon course in Los Angeles and attracted over 1000 entrants. Favorable racing terrain, good conditions (it started at 06.30), and the Olympic spirit brought personal bests by the dozen.

Julie Brown, who had dropped out of the Atlanta race, set the fastest time ever in a women-only race, winning in 2:26:26. In the third fastest time of 1983 she finished more than seven minutes ahead of Germany’s Christa Vahlensieck whose 2:33:24 at age 34 was a personal best in a career spanning more than a decade, in which she beat 2:40 28 times. Marianne Dickerson, in third (2:33:44) improved by 10 minutes and went on to win a silver medal in Helsinki in 2:31:09.

The finale of the Avon International Marathon Circuit came in Paris, three weeks after the Los Angeles Olympic marathon for women became a reality. Lorraine Moller raced through the dense parkland of the Bois de Boulogne – the site of the 1900 Olympics – to capture her third Avon title a scant 18 days after finishing 5th in Los Angeles.

All the runners could hardly help but be amazed at the progress made in opening up the world of distance running to women. The Avon program infused enormous amounts of both money and enthusiasm to help the governing bodies of sport carry out their mandate to provide sporting opportunities for all.