Opinion

05 October 2015, 7am UTC

Drug runners

You can be excused for being dumbfounded by the recent rash of commentary that has broken out over doping. The nature of the debate is designed that way. Each side has its experts hauled in to support or demolish the contentions of attention-grabbing headlines. The shouting match masquerading as debate is moved on by anything that can be portrayed as a new development. The frenetic pace dictated by the need to push the story inhibits any consideration of how we got into this sorry mess in the first place.

At one time distance running was one of the cleaner disciplines under the athletics “umbrella”. Why? Because there was nothing much that could be taken to enhance performance. The early cases of doping in distance running, just over 100 years ago at a time when it was temporarily cash-rich, were decidedly performance-inhibiting: consuming brandy or strychnine as a ‘pick-me-up’ more often had the effect of a ‘put-me-down’. An ashen-faced Thomas Hicks won the 1904 Olympic Marathon in St Louis after being administered with strychnine sulphate (a common rat poison) mixed with brandy.

At the next Olympic Games in London one of the race favourites, Tom Longboat, was apparently going well at 17 miles but forfeited the race immediately after receiving the ministrations of his trainer.

In the wider sport athletes in the sprints, jumps and throws could clearly boost their performance through the use of stimulants and anabolic steroids. These were events in which Soviet bloc countries performed well, especially on the women’s side. Yet the only standout distance runner was Waldemar Cierpinski. Steroids build muscle and aid recovery from hard training so should yield benefits to distance runners as they do to those in the more explosive strength-based events. Yet it seemed not enough to really upset the form book.

It was not until 1968 that a distance runner chanced upon a form of doping that vastly boosted his performance. It should have been obvious: the limiting factor in endurance running is the delivery of oxygen to the muscles. The bearers of oxygen are the red blood cells. More red blood cells equals more oxygen getting to the muscles.

After disappointing performances a Finnish steeplechaser was diagnosed as suffering from anaemia and received a blood transfusion. Soon afterwards he set a world record; blood doping was born.

When blood is withdrawn the body quickly replaces it. Meanwhile the extracted blood is centrifuged to extract the red blood cells and these are stored and then reinfused before competition to achieve a higher concentration of red blood cells and an enhanced ability to deliver oxygen to the muscles.

Tom Reilly, Professor of Sports Science at John Moores University in Liverpool, cited research which showed that: “[male] runners over 10km displayed improvements of over one minute… the characteristic change is that runners do not slow down in the later parts of their races”.

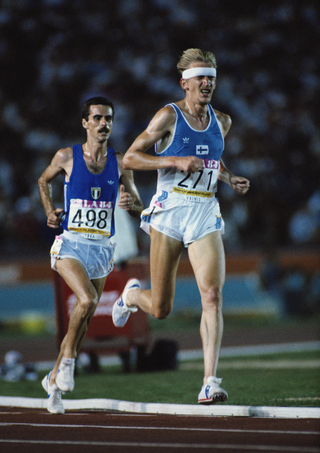

From the early 1970s Finnish runners enjoyed remarkable success, and there were those at the time that regarded them as having “suspicious profiles” not in today’s terms relating to their blood samples but in terms of their performances.

Alberto Cova, World 10000m champion in 1983 and Olympic Champion in 1984, testified to participating in a systematic programme of blood doping prior to these performances. But blood doping was not against IAAF rules until 1985. That it became so was in part stimulated by the performances of members of the US cycling team at the 1984 Los Angeles Olympics, who were reported as openly boasting of having received transfusions.

To blood dope requires laboratory facilities and the connivance both of those who operate them and those who pay the bills. Because of this it tended to be the athletes of certain nations that fell under suspicion in the 1970s and 1980s.

In the late 1980s an injectable synthetic hormone became available, recombinant erythropoietin (rEPO), which stimulates the bone marrow to produce more red blood cells. Originally developed for kidney dialysis patients it was quickly taken up by endurance athletes, primarily cyclists, to boost performance.

But in the early stages this was done more or less by trial and error and tending towards the presumption that “if it’s good, more must be better”. A higher concentration of red blood cells (“haematocrit”) makes the blood thicker and harder for the heart to pump around the body.

Between 1987—1990 19 Dutch and Belgian cyclists died in circumstances that indicated possible abuse of rEPO. Deaths generally occurred while the body was at rest and the heartbeat at its lowest so that the heart was unable to do the work of pushing the blood around the body.

In later years cyclists would use heart monitors linked to an alarm which would indicate when their heartrate was slowing to a dangerous low. They would then jump out of bed and pedal their turbo trainers to restore a ’normal’ heartrate. They would also learn what dosages could be directly life-threatening. The world governing body of cycling set a haematocrit level of 50% above which they would refuse to allow a cyclist to compete on health grounds. Normal levels of endurance athletes are around 46% but can be raised slightly by sustained training at altitude.

Runners and their managers came to the party later but benefitted from the hard-won knowledge of the cycling community. Despite the IAAF’s 1985 ruling against blood doping there was no effective test for rEPO and hardly any danger of being caught out by testing.

In the absence of ‘blood passports’ and blood profiling so much talked about in the latest surge of interest in doping matters it was the performance profiles that raised suspicions – although without ‘hard evidence’ these could not be acted upon.

There were runners against whom I competed in my marathon career (1981—1994) who showed elements of such a profile: those who had levelled out as 2:11 performers but who suddenly jumped to 2:08; those who trailed by 100m at 35km but suddenly made it up within the next kilometre. As a career athlete you can’t afford to dwell on your doubts but have to suspend disbelief simply in order to maintain a competitive attitude.

What has fuelled competition throughout the last three decades and more has been the coming of professionalism to what was supposedly an amateur sport. When significant prize money arrived on the scene with the big-city marathons it greatly intensified the incentive to cheat.

Twenty-two years ago the athletic world was stunned by performances of a small group of Chinese women who emerged under the tutelage of a ferociously disciplinarian coach. They broke all track distance world records from 1500m to 10,000m* with a recipe for success purportedly based partly on ingesting such exotic nutrients as caterpillar fungus and turtle blood. Such was the credulousness of the western media that this was reported on front pages of national newspapers. These stories served as a smokescreen against questions over what dietary aids might really produce such a uniformly dramatic improvement in the performances of that particular training group.

At the time there was also a naïve media acceptance of the performances of Kenyan and Ethiopian athletes as ‘natural’, without need of enhancement through doping. Just as professionalism in athletics had been resisted so were the consequences of globalisation denied. Runners might emerge from rural Kenya but they soon passed through the hands of western agents and handlers who all stood to gain substantially from the athletes’ success. And within their own countries emerging runners hoping to get themselves noticed would quickly realise that they would need all the enhancements they could get hold of, by whatever means.

In the post-Lance Armstrong era the media have finally woken up to what was known 20 years earlier but, with one or two notable exceptions, it’s just to spin the story rather than to uncover the facts. No one has yet plumbed the depths to which we have sunk, and it’s hard to identify anyone who might have the incentive to do so. In the Tour de France it took policemen kicking doors down to get a glimpse of the extent to which doping had penetrated the sport, yet Lance Armstrong’s long dope-assisted dominance started after this had happened.

Federations, race organisers and athlete managers are caught in the middle of the morass. Of course they want to clean up the sport, as much as they want to sustain the geese that lay the golden eggs.

- The top 6 women’s times ever at 3000m were run on 12–13 September 1993 by members of this group, and the 10,000m record established is still more than 20 seconds faster than any other woman has ever run.