Opinion

01 January 2011, 8am UTC

Looking back over 2500 years

On 31 October Athens staged its largest ever international Marathon race in tribute to the 25th century anniversary of the Battle of Marathon and original Marathon Run.

Both these events were of long-lasting political and cultural significance for the democratic world. In modern times they provided the inspiration for the establishment of the popular Marathon Race.

This inspiration has arisen from the dubious historical claim that there was an ancient solo runner who supposedly died of exhaustion after delivering the message of victory over the invading Persian empire. The truth is more inspiring. Tribute should be paid to those who really staged the 42km feat – in fact more like 45km – namely the 11,000 soldiers who, after a fierce battle and loss of comrades at Marathon, actually did make a heroic mass run back to Athens. This was a run more real, meaningful and spectacular than the legendary but accepted tale of the solo runner. In doing so, they saved the ancient city state from a second attack and capture on that same day and helped protect the subsequent evolution of Athenian and global democracy.

European romantics, historians and sports writers have played a key role in developing the myth of the single runner. However important a source of inspiration that legend has proved to be, in doing so they have failed to give credit where it is really due.

The marathon race, the dramatic, closing event to every Olympic Games and now a spectacle staged annually in more than 700 cities around the world, was inspired by two parallel running feats of endurance that purportedly took place before and after the famous battle in 490 BC. About a week before the battle a runner called Philipides or Pheidippides (both names have been used in ancient texts) is said to have run a total of about 500km to Sparta and back in two days to try to raise military support for Athens against the invading forces of the largest Empire the world had ever known. That run is commemorated nowadays by the ‘Spartathlon’, a run from Athens to Sparta, which covers only the first half of the course that Pheidippides supposedly ran.

Modern writers also claim that the same runner, or someone like him, ran the 26 miles (42km) from the Marathon battlefield to the city to announce the unexpected victory over the Persians, and then died of exhaustion after crying out “Rejoice, we won!” It is this legend which, 24 centuries after the battle, inspired French and British historians, artists and romantics to pursue the establishment of the Marathon Race at the first Olympics of 1896 in Athens. It has since swept the world, with major, high-profile races taking place every year in such cities as Boston, New York, London, Berlin and Tokyo, embracing all continents and even inspiring such events as the North Pole Marathon.

However emotional and inspiring such stories are I am convinced neither of these two long-distance runs took place – nor could there have been any tactical logic in attempting them. In both cases – the mission to mobilize Spartan help and the delivery of news of victory at Marathon – it would have been irrational and potentially disastrous for an invaded city-state to rely on a solitary runner. Both missions must have been carried out more safely and effectively by a team of horsemen, along with the well-tested military signals of the time (smoke signals and sunray deflections from shields or concave objects).

What took place in terms of running was something far more necessary and admirable. It was clearly recorded by Herodotus, the ancient thinker and traveler generally referred to as ‘the inventor of the writing of history’, who was the only almost original source on the Greco-Persian wars. But for some inexplicable reason this running feat has been almost totally ignored by modern historians and writers.

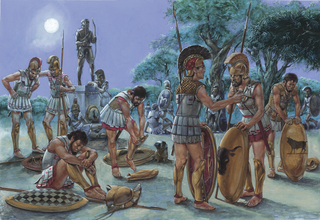

Herodotus wrote that there was a marathon run by 11,000 armed, exhausted but emotionally charged Greek hoplites or foot-soldiers (10,000 Athenians and 1,000 Platean allies). This was no mission to deliver a message but a real life-or-death race between the battle-scarred soldiers and the Persian fleet. The battle had not ended and the soldiers, with their armour and clothes soaked in blood, sweat and tears, ran “as fast as their feet could carry them” about 45km back to their Herakleion military camp at Kynosargus hill in Neos Kosmos. From here they could overlook the beaches of Athens’ Phaleron Bay, where the second Persian attack was expected.

They won the race. They arrived in Athens before the Persians got there and could land soldiers and horses at the doorstep of the city. The Battle of Athens in 490 BC was won by military means in its first half, and by a race in its second and final part. This is the only mass race of global significance recorded in history, and makes perfect sense (unlike the solo Sparta or Marathon runs).

The military goal of the Persian invaders, after a three-month conquering sweep across the Aegean Sea, were not the empty fields, shores and deadly swamps of Marathon. It was to capture Athens and then nearby Corinth and Sparta,

the only Greek states which continued to reject the Persian ultimatum and blocked the empire from entering the European continent. (The Greek city states of Eretria and Karystos on the nearby landmass of Evia had been destroyed and their people enslaved only shortly before the Persian pincer attack on Marathon and Athens).

Herodotus’ reference to the alleged 500km solo run to Sparta and back reads like one of his more colourful fairy tales. The run, over very rough and dangerous territory, was equivalent to 12 continuous marathons, and based on accounts by elderly survivors who spoke to the historian some 45 years after the battle. Resorting to the supernatural to convince his audiences of the superhuman character of this alleged feat, Herodotus wrote that as the runner was about to collapse and give up at the start of his return trip, after gaining only a vague promise of support from the Spartans, the half-goat, half-human pagan god Pan appeared to him from the sky. Pan demanded that in return for giving him strength to complete the run, Pheidippides would persuade the Athenians to have Pan worshipped equally along with the other gods.

Similarly, when the Persian fleet was making a second encircling attack directly on Athens, despite having been repelled at Marathon a few hours earlier, it made no sense to send a solitary ‘Marathon runner’ back to the city to announce an inconclusive victory. The battle-weary soldiers were the real Marathon runners, rushing back to the second front. They completed the victory by blocking the Persians’ second landing and their southern entry to the European continent. Confronted by the unexpected sight of the Athenian army back in position in Athens, Herodotus explains that the invaders were forced to sail away.